“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

The Engine Control Module (ECM) is always keeping an eye on the amount of fuel it is adding to the cylinders, and it’ll throw a code when it figures it can’t keep the mixture right where it needs to be. You might see codes like “system rich” or “system lean,” and they could pop up for one or both banks of the engine. Of the two, the “system lean” ones show up way more often. Here are some quick tips on pinning down what’s causing a lean condition.

The ECM is the boss of fuel delivery to the engine, and it has to keep that air/fuel mix super close to ideal to prevent the catalytic converter from getting pissed off. The only way it knows if it’s got the ratio right is from the oxygen sensors’ feedback. Those sensors clue the ECM in if the mix was too rich (extra fuel) or too lean (not enough). Based on that, the ECM tweaks things, and we can spot those changes on our scan tool as fuel trim data Parameter Identifiers (PIDs).

There are two to pay attention to, in particular: short-term (STFT) and long-term (LTFT). STFT is the ECM’s quick fix for right-now changes, and it’s needed to get an accurate air/fuel read from the oxygen sensor. LTFT is more like a learned habit based on what the ECM noticed from STFT trends. That’s the basics—anything deeper would need its own deep dive! Hit up our training site and dig through the resources there. Searching “P0171” should kick things off for you.

If the ECM keeps piling on fuel corrections short-term, the long-term will pick up on that pattern and start tweaking injector on-time upfront. If long-term hits its max limit and short-term’s still pushing for more, bam—the ECM sets that “system lean” code. It just can’t fix whatever’s demanding all that extra fuel.

So, is the lean issue from too much air sneaking in, not enough fuel getting delivered, or some sensor straight-up lying?

When I’m troubleshooting a fuel trim code like this, my first move is checking the freeze frame data tied to the code to see what the engine was doing when it happened. Was it at idle—low RPM, barely moving? Or cruising—higher RPM, engine warm, highway speeds? That stuff points me in the right direction fast.

On engines with a Mass Airflow (MAF) sensor, lean codes at idle usually mean air’s getting in where it shouldn’t. At higher RPM, it’s often fuel delivery screwing up. And yeah, both could be from a shady sensor.

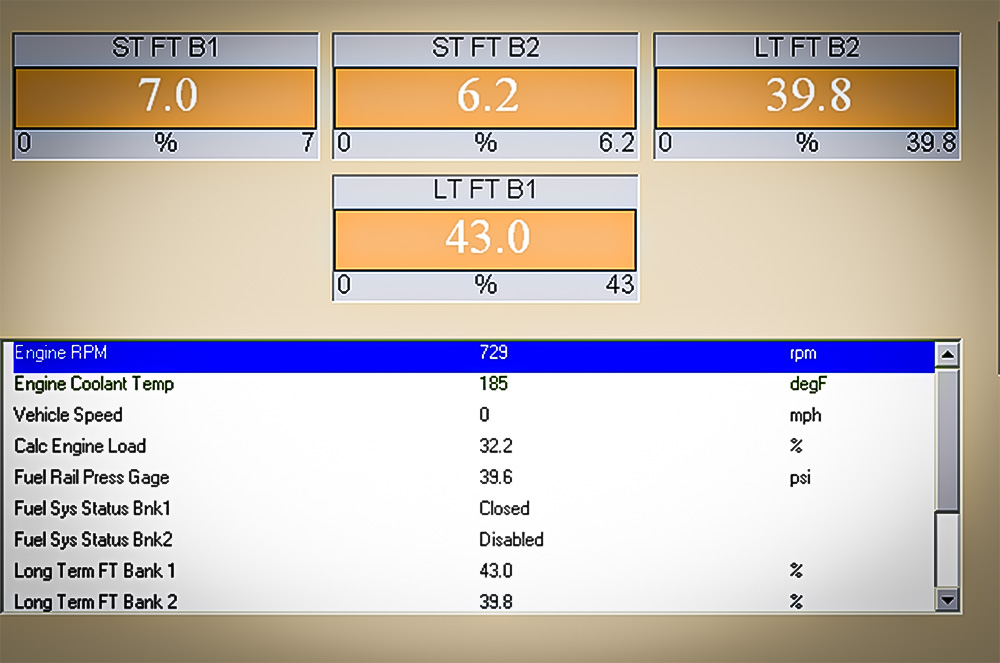

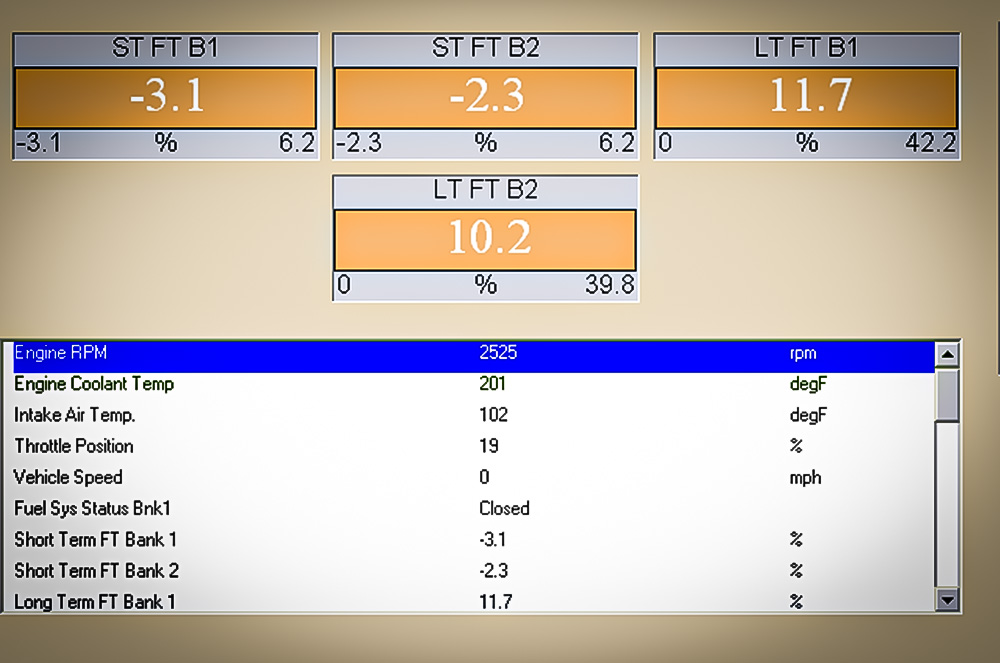

I like using the MAF as a helper tool. Fire up the engine and let it warm to operating temp. Jot down STFT and LTFT and add ’em up. That’s Total Fuel Trim (TFT). STFT bounces around; that’s normal, just average it out. Do this for both banks if it’s a V engine. Then bump RPM to about 2500 and grab the numbers again.

If TFT’s way higher at idle than at 2500 across the board, I’m betting on an air leak. Why? Leaks don’t let in tons of air, but at idle with the throttle shut, that extra air is a bigger chunk of the total intake, so it messes things up more.

If TFT’s about the same, skip the leak hunt. It’s probably not that. Check if the MAF is reading right and that fuel delivery is on point. Not just pressure but volume too.

Notice the RPM PID—the ECM is adding a ton of fuel at idle. Screenshot: OTC Nemisys scan tool by Pete Meier.

At 2500 RPM, fuel trims are almost normal. This is unmeasured air entering the engine somewhere. Screenshot: OTC Nemisys scan tool by Pete Meier.

Back in the day, I’d grab carb cleaner and spray around the intake to find vacuum leaks. If it were big, the engine would rev up from sucking in the flammable stuff. Or at least, you’d see the oxygen sensor go rich when the spray hit the spot. You can still do that, but I prefer using my EVAP tester’s smoke feature.

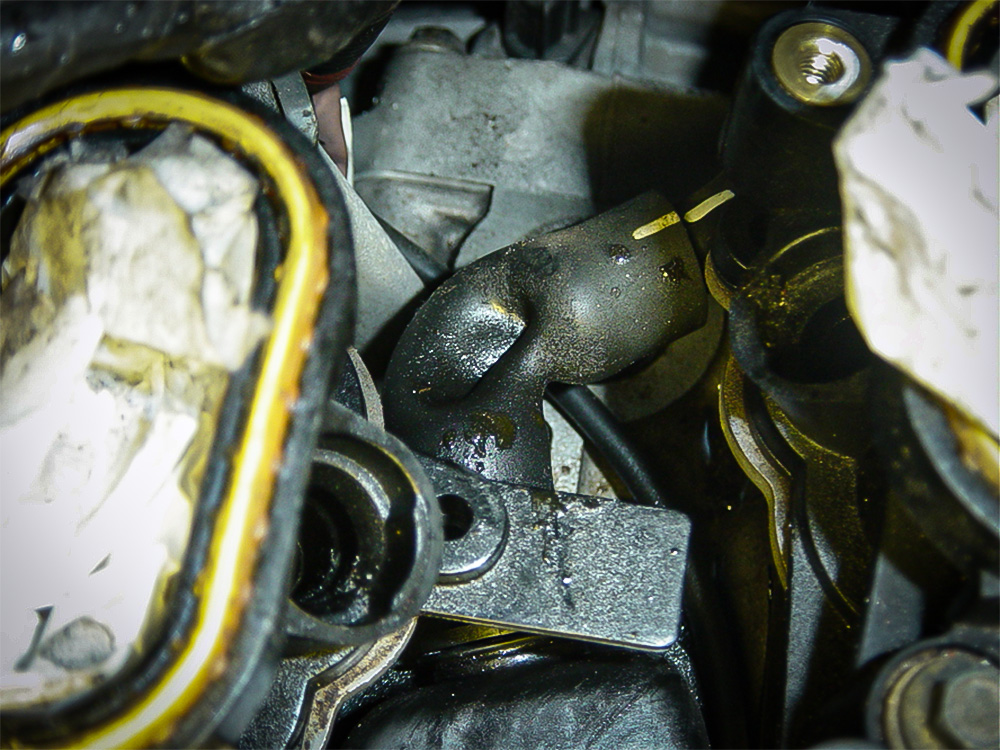

Pump smoke into the intake and watch where it puffs out. I’m scanning for any air sneaking past the MAF, like the boot from the MAF to the throttle body. Usual suspects include intake manifold gaskets and PCV hoses. Less common are engine seals, the oil dipstick tube, and even the oil cap, especially if the PCV system has trouble, like a stuck-open valve.

I can’t see what component is leaking, but at least I know where the leak is. Photo: Pete Meier.

This oil-soaked PCV boot is the culprit. Photo: Pete Meier.

If the MAF is fibbing, the ECM’s working off bad info and that lean code might be its fault. Most modern MAFs are hot wire or hot film and they get dirty easily. When contaminated, they underreport air flow. The ECM adds fuel based on the lie, but since more air actually showed up, it’s lean city. The oxygen sensor snitches and the ECM cranks up trims to compensate.

One PID I watch is Calculated Load. It’s basically the engine’s volumetric efficiency (VE) as a percentage. If I suspect the MAF, I take a test drive recording load, RPM, trims, and gear. On a safe road, from a roll in first, floor it wide open till it shifts to second. Check the data right before the shift—that’s peak effort. If the load’s low (Calculated Load under 70-80%) and trims are adding fuel, blame the sensor. If trims are fine, look for breathing issues such as a clogged exhaust, a dirty air filter, or cam timing. Anything that is preventing the air from getting in and back out again.

If the fuel system’s slacking on demand, that can trigger lean codes. Testing pressure and volume is standard stuff, so I won’t bore you with basics. But one trick I use on that test drive is to do a near-WOT acceleration to 60-65 mph (on a legal road, obviously) while recording oxygen sensor data. They might dip lean when you mash the pedal, but they should bounce back quickly. If they stay lean under load, dig into fuel delivery.

Always check volume, not just pressure! I’ve seen plenty where pressure is on spec but volume isn’t, and the fuel pump can’t supply the engine with enough fuel under heavy load.

Ultimately, “system lean” codes don’t have to be a headache if you let the data do the heavy lifting. By leveraging your scan tool’s fuel trims and freeze frame data, you can target the actual failure: whether it’s a vacuum leak, a tired fuel pump, or a dirty MAF sensor.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.