“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

In 1908, a young inventor named Byron Carter pulled over to help a stranded driver start their car. This goodwill gesture ultimately ended Carter’s life, but also inspired a new automotive era.

This was back when most vehicles on the road had to be hand cranked to start. To do this safely required following a careful, step-by-step procedure. A removable handle connected through a hole in the grille to the front of the crankshaft. After priming the engine, adjusting the throttle and timing the ignition, a turn of the crank was enough to mobilize the pistons and get the engine running on its own power.

If you didn’t follow this process exactly, the engine could backfire, violently jerking the crank. That’s why you always had to make sure to only turn the crank with your left arm, and avoid wrapping your thumb around it, so if the crank handle spun backward it would pull you in a more natural motion, and not break your arm.

Still, broken wrists were common enough that surgeons coined a term for a particular type of injury most often seen in professional drivers: the chauffeur fracture.

“In the fracture from the ‘back kick’ of the starting handle, there is no impaction or splintering,” described one orthopedist in 1904. “The hand is violently dislocated backward, and the ligaments at the wrist simply tear off the articular surface close to the lower end of the bone, commonly just above the base of the styloid process.”

Bryon Carter would’ve known all this like the back of his … hand. He was a motor vehicle pioneer who had founded the Jackson Automobile Company and the Cartercar company in Michigan, which used a unique friction drive design in its vehicles, and was eventually acquired by General Motors.

But, for whatever reason, he was unprepared that winter in Detroit when he stopped to help a woman with a stalled Cadillac. The engine backfired and the crank broke his jaw. He died not long after, with different sources saying it was due to either pneumonia or gangrene.

Carter’s friend, Henry Leland, the founder of Cadillac, was heartbroken. “The Cadillac car will kill no more men if we can help it,” he said.

Around the same time, not far away, another inventor named Charles Kettering had been working on something that could eliminate the hand crank altogether. Kettering had already invented a motorized replacement for the hand crank on cash registers, and was tinkering with other solutions for automotive engines. Leland was impressed, and the next year he started ordering parts from Kettering and his business partner, who started a new production company to handle the work, named the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company, or Delco.

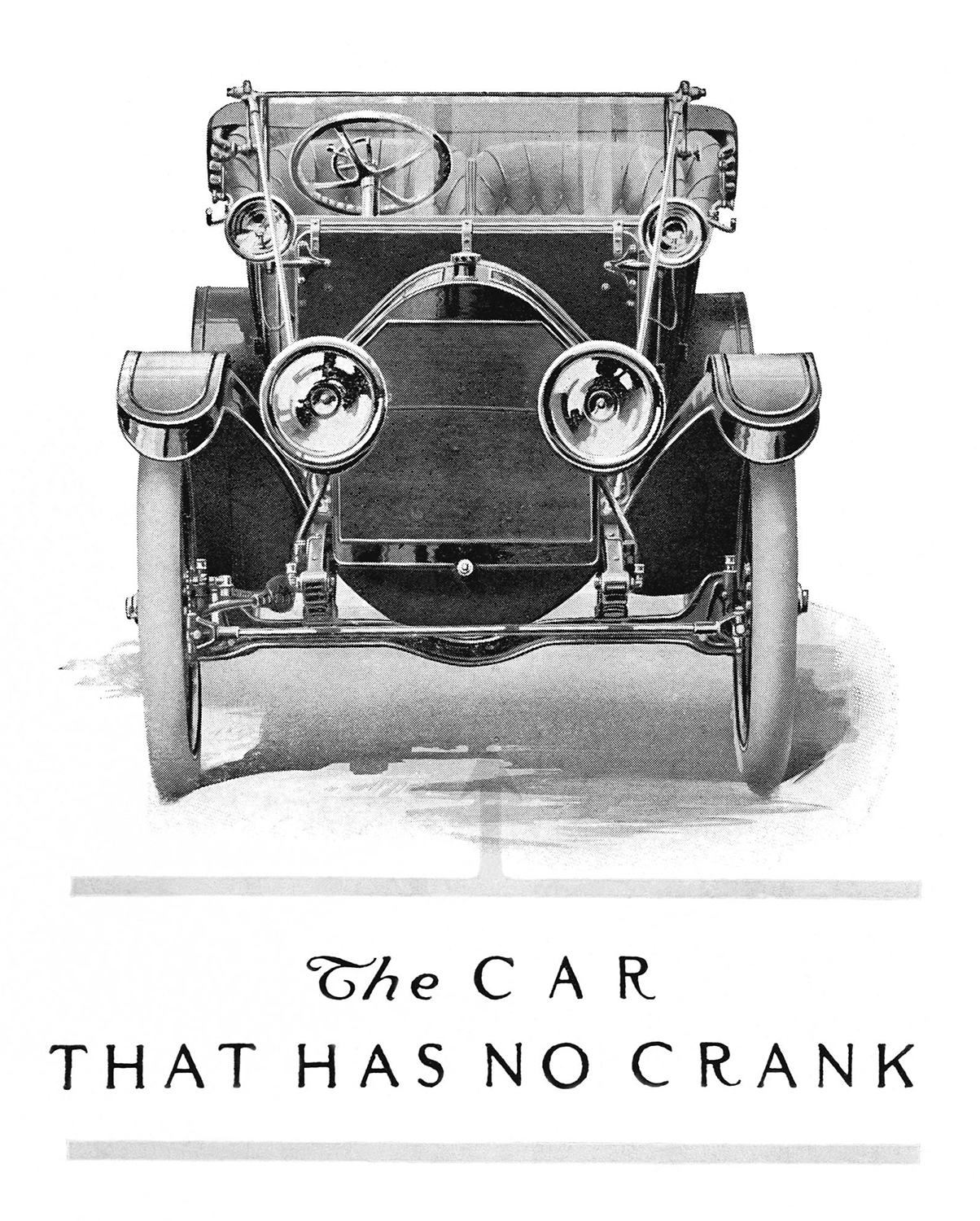

At this point, an electric starter motor had already been conceptualized and patented, but it wasn’t yet practical for mass production on an automobile. Leland tasked Kettering with improving on it, and he soon patented his own design. The new motor appeared on the 1912 Cadillac Model 30, a four-cylinder, 40 horsepower innovation that also featured some of the first electric headlights. It was marketed as “The Car That Has No Crank,” and it instantly doubled Cadillac’s sales. A Cadillac brochure from the time called it “the greatest achievement for the advancement of the motor car since the inception of the industry.”

Notwithstanding the hilarious grandiosity of marketing materials from the early 20th century, many people believe the starter motor was the single car part that most transformed the automobile from a luxury fascination to something everyone could own and use regularly. It not only eliminated the danger of hand cranking, but it also made it possible for anyone, of any strength and stature, to start an automobile. For that reason, Cadillac also marketed the car toward women for the first time.

This new accessibility created by the starter motor also put the nail in the coffin of electric vehicles, which at the time were still competing with gasoline-powered cars and trucks for supremacy. With greater range, lower cost, and now the same ease of ignition, internal combustion engines took off. In 1912, there were less than a million vehicles on the road in the United States. In a decade, there were 12 million, which was more vehicles per capita at that time than Asia and South America have today.

Starter motors are simple in concept – an electric motor that cranks an engine rather than your bare hands – but they’re also fascinatingly complex because of all the critical complications that come into play. They have continuously evolved quite a bit over the years as well. For instance, the foot pedal switch of Kettering’s design has long been replaced with a solenoid to turn on the high current needed to power the starter motor. The technology has evolved much further to enable today’s more sophisticated systems, such as stop-start capabilities that constantly turn the engine on and off to prevent idling and increase fuel economy.

In addition to jumpstarting the creation of a nation of drivers, the origin of this car part is still evident in everyday life. GM eventually acquired Delco and still owns the rights to the name, which it used to create the ACDelco brand in 1974. Kettering became head of research at GM for more than 20 years. He died in 1958 holding nearly 200 patents, and having led many other projects that in some ways changed the world.

One of these other inventions that is remembered less fondly was first explored when people starting blaming strange engine noises on their electric starters. At first, Kettering and others couldn’t explain or solve the common pinging or knocking sound. It turns out it didn’t have anything to do with his starter, but with the octane rating of the fuel being used. By 1921, he and his team of researchers introduced a new creation that solved the problem and improved vehicle performance, but also caused a world of other problems: leaded gasoline. But that’s a whole other story.

This article is from an occassional series called The Best Part that tells the fascinating stories behind car parts. Have any ideas for other parts with cool backstories? Let us know in the comments below.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.