“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

The air in Detroit during the 1960s was so polluted that mothers were scared for their children to play outside. In certain places, you couldn’t see the sun at noon, and buildings had to be cleaned or repainted every six months. Some people wrote letters to congressional leaders saying they felt guilty every time they started their car.

“The automobile and petroleum industries are enormously powerful,” one resident wrote to his senator. “Do you have the courage to stand against them?”

Detroit was certainly not alone. Photochemical smog, a brownish haze produced when solar radiation reacts with hydrocarbons and nitrous oxides in the air, was infamously common in heavy commuter cities like Los Angeles.

Compelled by a growing, bipartisan environmental movement, Congress took action by passing the Clean Air Act in 1963, which was significantly expanded in 1970 – the same year as the first Earth Day – and included much stricter regulations for automakers. Specifically, it required vehicle manufacturers to cut emissions of NOx, hydrocarbons, and carbon monoxide by 90 percent by 1975. It was stringent, but the federal government was furious at manufacturers, even alleging that Detroit’s Big Four (then including American Motors) had conspired for years to prevent this from happening.

How the auto industry would actually meet those new standards was not clear at first. Lee Iacocca, who was then president at Ford, predicted that the industry would have to flat-out stop producing cars.

“No matter how much we spend and how many people we assign to the task,” he said, “we do not think we can do it by Jan. 1, 1975. Under this bill we would be directed to reduce all emissions by 90 percent even if nobody knows how to reduce emissions by 90 percent.”

Indeed, the act didn’t specify a certain technology, so engineers set to work evaluating their options. However, there was already an option that had been discussed for decades: catalytic converters.

The average person doesn’t know or think a lot about catalysts, but they’re a part of everyday life. Catalysts are simply atoms or molecules that react with other molecules to facilitate a subsequent reaction, which people often use to create a more desirable result with less effort. A molecule temporarily bonds with another molecule so that it becomes easier to turn into another molecule. They’re middlemen, making it easier to transform something, without transforming themselves.

When it comes to automobiles, people had long discussed the possibility of using catalysts to convert harmful exhaust gases into harmless ones. The idea that this would be necessary to reduce the negative effects of combustion engines was proposed as early as a year after the first Ford Model T went into production.

Eugene Houdry is widely credited with spearheading the technology through the mid-20th century. Born in France in 1892, he served in the very first tank corps in World War I, and afterward he took up road racing. That sparked his interest in high-performance fuels, and he became an engineer working on various methods of producing higher quality gasolines using catalysts. In 1930, he moved to the Greater Philadelphia area, where he revolutionized the industry by creating a process called catalytic cracking. By breaking heavy hydrocarbon molecules into lighter ones, refineries were able to produce higher octane gasoline much more efficiently. (Much like the turbocharger, this improved fuel helped Allied planes outperform their Axis enemies in World War II.)

However, in the 1950s, Houdry grew concerned with the detrimental byproducts of his work. He founded his own company producing devices that would use catalysts to convert the undesirable results of combustion into more innocuous outputs. From his workshop in Ardmore, Pennsylvania – not far from Dorman’s headquarters – he proved it possible by developing catalytic devices for a nearby industrial plant that had been plaguing the surrounding community.

“Houdry’s process is quite simple,” reads a Time magazine article from 1952 on his work at an Allentown factory. “The catalytic units are arranged in layers in the chimneys, and each unit has 73 porcelain rods coated with a thin film (only .003 inch) of alumina and platinum alloy. This coating is the catalyst, which combines with oxygen in the atmosphere to burn up noxious wastes ….”

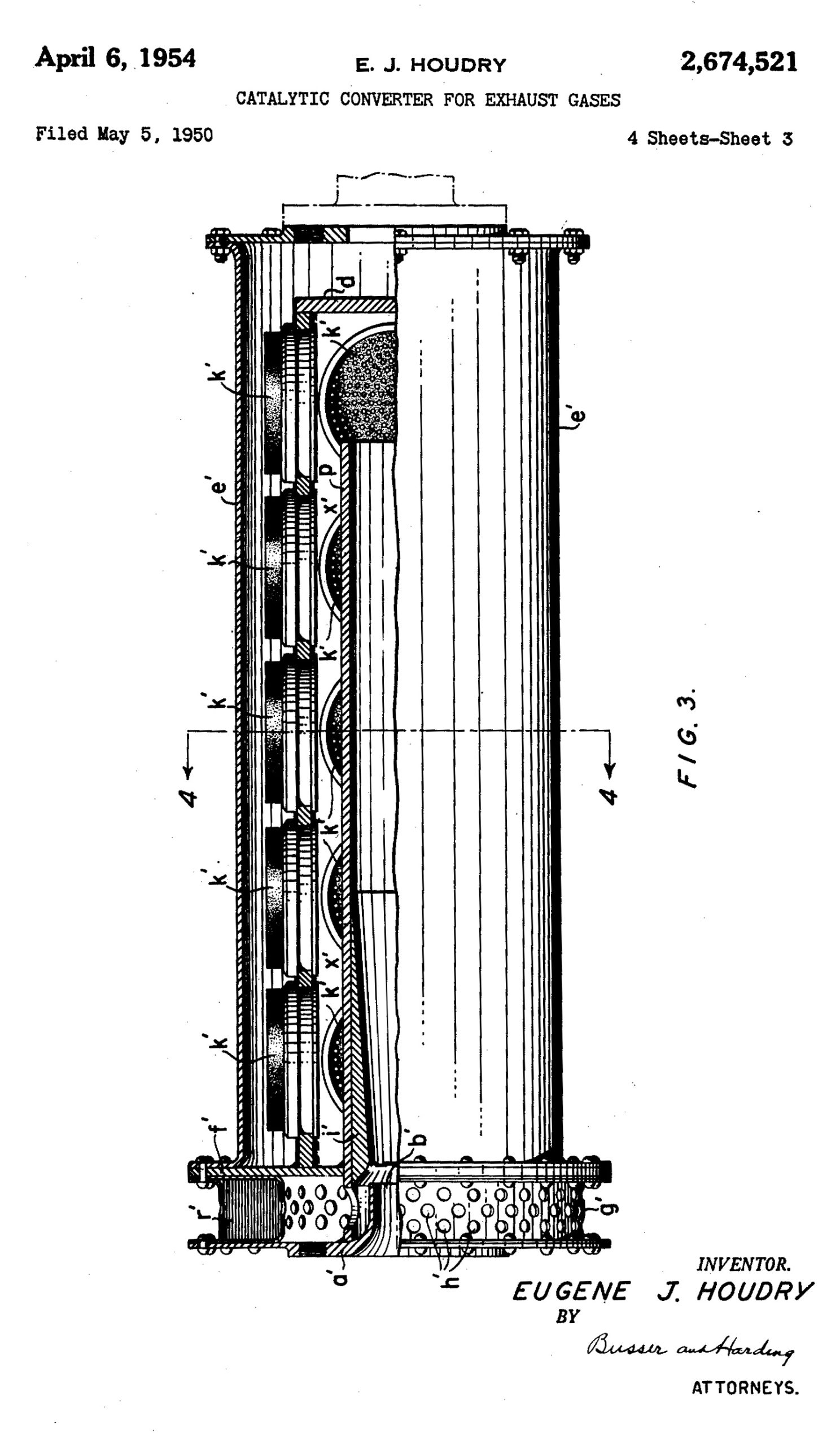

After those initial successes, he turned to automobiles. He patented a new device, a catalytic converter for exhaust gases, in 1954, and the media speculated whether they would be an end to smog. An amazing 1955 article in Popular Mechanics about his invention describes so splendidly how these converters work that I have to just quote it at length:

“A catalyst is like a heckler who prods two other guys to fight. A cat never does much fighting himself – he’s needed to keep things stirred up.

“In your car’s exhaust pipe the trouble is that nobody wants to fight. The waste hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide coming down from your engine aren’t hot enough to mix it up with oxygen – in other words, burn. Like snakes on a cold day they are too lazy to fight.

“So Houdry throws in a cat, and – wham! – a fight starts. Oxygen from the air leaps with a snarl at the smelly stuff. While the cats glow with the heat of the fight, oxygen rips the hydrocarbons apart. The hydrogen joins some of the oxygen to form water (H2O). And the widowed carbon is swallowed by other oxygen, burning into harmless carbon dioxide (CO2). Deadly carbon monoxide (CO) gets the business, too. Attacked by oxygen, it also burns to (CO2).”

Man, they really knew how to write in the ‘50s, huh?

Anyway, automakers did not take up this promising new technology until after Houdry’s death in 1962. It would be another decade until automakers started seriously planning for these new “scrubbers” to meet the stringent federal requirements.

By many accounts, General Motors was the first automaker to view catalysis as the solution. CEO Ed Cole had started hiring chemists in the ‘60s to investigate, including one from DuPont named Dick Klimisch, who eventually earned the (somewhat derisive) nickname “Captain Catalyst” from colleagues.

“I was just the first person in GM who knew how to spell catalyst,” Klimisch quipped years later.

He and other researchers at the time respected Houdry’s work and saw the potential, but there were still massive engineering challenges to overcome. A fantastic 2004 article from Invention & Technology magazine called “Doing The Impossible” equated the behind-the-scenes scramble to NASA’s Project Apollo.

“Like the race to the moon, this would take a crash program of research and development,” wrote author Tim Palucka. “The 1975 automobiles would be introduced in September 1974, so there would have to be a factory running at full speed turning out millions of the emissions-cleaning devices before then. The car companies would have to start tooling up for manufacturing these models early in 1974, so all specifications would have to be finalized late in 1973, meaning that all development and testing would have to be done by earlier that year. The makers had two or three years to go from basic research to manufacturing.”

Captain Catalyst put it more succinctly: “We went through hell.”

First, they had to overcome the problem that Houdry encountered when he tested his converters on automobiles – leaded gasoline. Whatever the design, the lead then put in gasoline to improve the octane rating would coat the catalytic surface, rendering it ineffective, a.k.a. “poisoning” it, after only a year or two of normal driving.

Seeing what was coming down the road, in 1970, Cole declared at a meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers that his company would stop using leaded gasoline starting with 1971 model years. That was huge, because GM was huge. They were the largest employer in the world, let alone the largest automaker, and now oil companies were incentivized to produce more unleaded gasoline.

With that hurdle out of the way, GM and Corning Inc. patented two different designs that would be first installed on 1975 model years. GM used a pelleted design, with aluminum oxide pellets coated in platinum and palladium, precious metals that had out-performed baser metals like copper and iron in testing. AMC and Nissan licensed this design, and Toyota used it as well, which led to a legal dispute with GM. Check out the first three minutes of the delightful GM video below for an illustration of how it worked.

Ford and Chrysler, meanwhile, used Corning’s honeycomb design, referred to as monolithic, which was also coated in catalysts. Producing this substrate, made of a specially designed cordierite ceramic, extruded through a die to produce hundreds of tiny chambers, with walls as small as two thousandths of an inch thick, was an innovation in and of itself.

“Having a major breakthrough is very rare in any company,” Rodney Bagley, a Corning engineer, said later. “In the catalytic converter we had two major breakthroughs: a new process and new materials that didn’t exist before.”

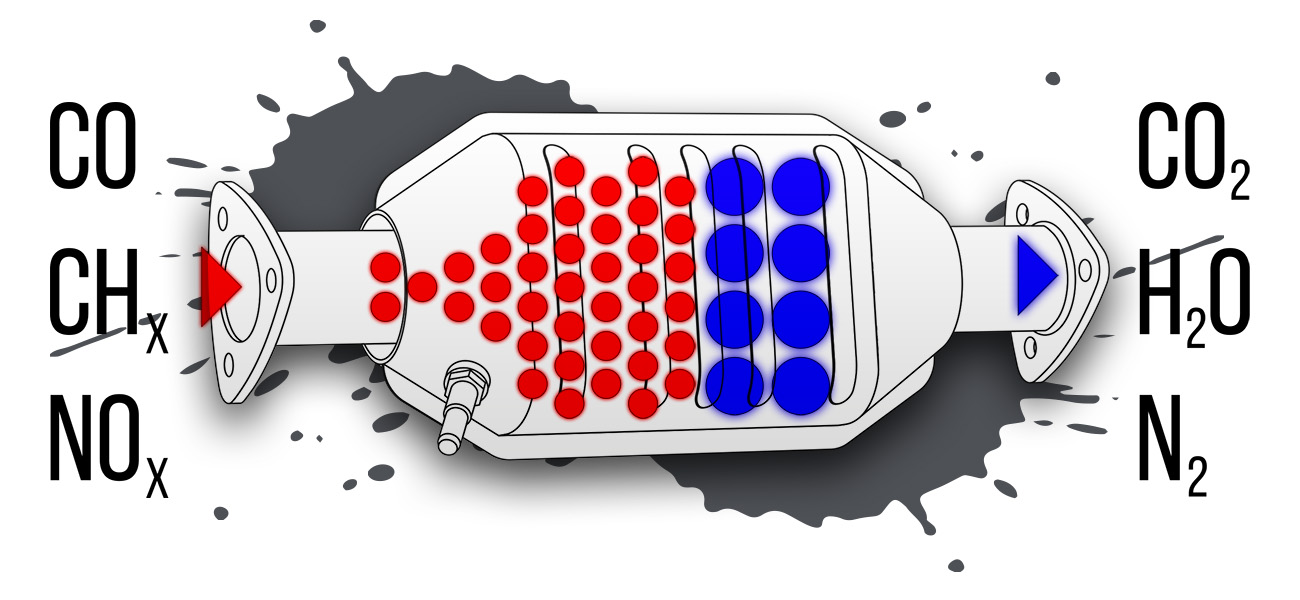

These designs did one thing, in two ways. The precious materials performed oxidation, meaning they facilitated combination with oxygen. That turned carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide, and hydrocarbons into carbon dioxide and water. For that reason, these were called two-way converters.

However, they still didn’t do anything about nitrous oxides, which the recently created Environmental Protection Agency granted extensions for car makers to control. Neutralizing these chemicals requires a process called reduction, which brought a third catalyst, rhodium, onto the scene. This extremely rare element reacts with nitrogen to pull it apart from oxygen, creating harmless nitrogen and oxygen. The first devices that could perform this trick, called three-way converters, were introduced in 1981.

While additional technologies have made these systems more efficient, the honeycomb design, coated in precious metals, performing both reduction and oxidation, remains the standard for catalytic converters even today.

Despite the engineering feats car companies had to achieve to get them into production, catalytic converters were hated by many before the first cat-outfitted car rolled of the assembly line.

Alan Loofbourrow, Vice President of Engineering at Chrysler, called it “the dumbest thing to ever happen to the automobile,” as quoted in a New York Times article titled “Catalytic Converter: Big ‘If’ of 1975”.

Automakers estimated the cost to the consumer for the new equipment was approximately $200 per vehicle, or more than $1,000 in today’s money. They also estimated they would spend over a $1 billion from 1975 to 1980 buying precious metals from two nations the U.S. did not really want to send more money to at the time: the Soviet Union, during the midst of the Cold War, and South Africa, during the midst of apartheid. (Both places remain the largest producers of these metals today.)

When complaining and increasing prices wasn’t enough, they found ways to sidestep. The law technically required cats on vehicles with gross weights of less than 6,000 pounds, so Ford introduced a new model in its F-Series line, between the F-100 and F-250, that had a GWR of 6,050, just dodging the requirement. It was called the F-150, and if it’s any gauge of consumer sentiment, it became the best-selling truck in America two years later and hasn’t left the top spot since.

The manufacturers were right about one thing – the initial designs could’ve used more testing. GM’s pelleted design was particularly problematic. These coated beads were packed in tightly to ensure the maximum surface for the catalysts to neutralize the exhaust, but they couldn’t be packed too tightly, or the exhaust couldn’t flow through.

As a result, the orbs still moved around a bit, eventually wearing down, losing their effectiveness, and clogging the exhaust. In theory, you could have the catalyst serviced by replacing the pellets, but car owners wouldn’t always be quick or willing to do so.

Compounding the issue was that converters rely on an ideal air-fuel ratio, but vehicles at this time were still carbureted, leading to mixtures that were often too lean or too rich to operate efficiently. (Closed-loop systems were introduced in the ’80s to make the mix precise and dynamic. Oxygen sensors and fuel injection contributed to the efficacy of closed-loop operation.)

As a result, it wasn’t unheard of to melt a converter, if not spew molten hot beads out the tailpipe. This fun article from CurbsideClassic.com tells a vivid story of the author’s parents’ vehicles hissing, emitting foul stenches, and altogether running poorly due to this failure-prone design.

Many people in those early days opted to remove cats from their vehicles. Over the years, though, designs improved and automakers were able to make vehicles more powerful and reliable than ever, making converters just another part of the car we take for granted. Until, ironically, people started removing other people’s cats.

As anyone who even casually follows the news knows by now, there’s been an epidemic of catalytic converter theft as the prices of the precious metals inside have hit record highs, and lowlifes have clearly identified these devices as easy targets during the pandemic. Thieves can slide under a vehicle, cut out the cat with reciprocating saw, and take it to a less-than-scrupulous scrapyard.

According to the National Insurance Crime Bureau, cat burglary has increased more than 1,200 percent from 2019 through 2022. According to a recent data analysis by Carfax, 153,000 converters were stolen in 2022 alone. That’s way more than had been reportedly previously in the media, because other accounts relied on insurance claims, while Carfax says their data scientists tried to account for the fact that not all victims have insurance coverage.

That’s spurred a new flurry of converter innovation, with researchers exploring more efficient and less expensive designs, and everyone from big companies to guys in their garages unveiling new anti-theft devices. Many repair shops have announced programs to install shields for their customers as well.

The government’s also stepping in once again. There are dozens of state laws that have been enacted to address the problem in various ways. A federal law, the Preventing Auto Recycling Thefts (PART) act, was just reintroduced in January, which would require automakers to put VINs on their converters to make them traceable.

It’s just the latest turn of events in what’s been a wild ride for this technology. In 50 years, it’s gone from revered, to reviled, to ignored, to invaluable. Along the way, one thing’s been consistent: catalytic converters certainly cause a reaction.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.