“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

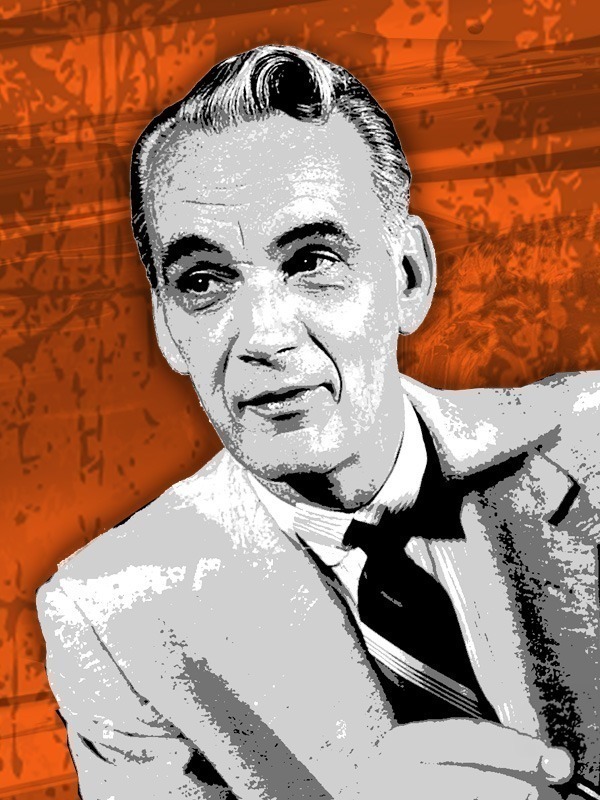

I’m a sucker for the sleek, smooth, and aggressive look of late 1950’s automobiles. As such, I owe a debt of gratitude to one man: Virgil Exner. In the 50’s, Exner was the head of styling at Chrysler, and he spearheaded the “Forward Look” of their cars, a look that Chrysler’s competitors attempted to copy in the late 1950’s with the Chevrolet Bel Air and Ford Fairlane, for example. In fact, Chrysler was, after Exner’s time there, considered a very high-end vehicle (Exner’s 300 series, for instance, really competed against Rolls-Royce) and Chrysler continued to ride that reputation for at least the next 20 years.

Virgil Exner was born September 24, 1909, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. In 1926 he went to the University of Notre Dame to study art but dropped out after two years because he couldn’t afford to continue paying tuition. He then took a job drawing advertisements for Studebaker trucks. After this, he worked in design for General Motors, where eventually he oversaw Pontiac styling. (Note that, at this time, Pontiac was its own unique brand of vehicle with its own bodies and engines, as opposed to what it became in later years, which was basically a rebadged Chevy.)

In 1938, automotive and industrial designer Raymond Loewy offered to double Exner’s GM salary to lure him to his industrial design firm, Loewy and Associates. Exner took the offer, and at Loewy’s company he worked on cars, including Studebaker’s 1939-40 models and World War II military vehicles. However, tensions between Exner and Loewy would soon brew. Many of Exner’s disagreements with Loewy stemmed from the fact that Loewy, as the owner of the company, would take credit for his designers’ work (which was common practice for industrial design companies at this time). While Loewy gained fame for Studebaker’s innovative postwar designs, many were actually Exner’s work. The friction between Exner and Loewy escalated to the extent that Roy Cole, Studebaker’s engineering vice president, suggested Exner work on alternate designs at home in case the company’s own delicate relationship with Loewy fell apart.

In 1944, after being sacked by Loewy, Exner was hired immediately by Studebaker as their Chief Styling Engineer.

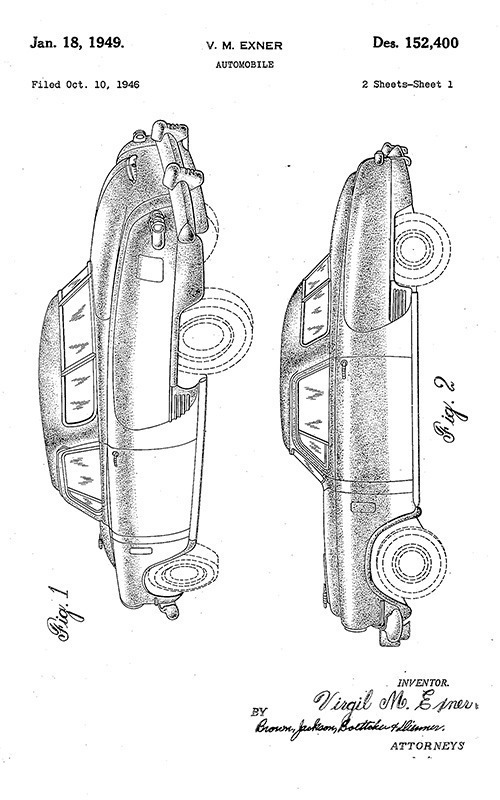

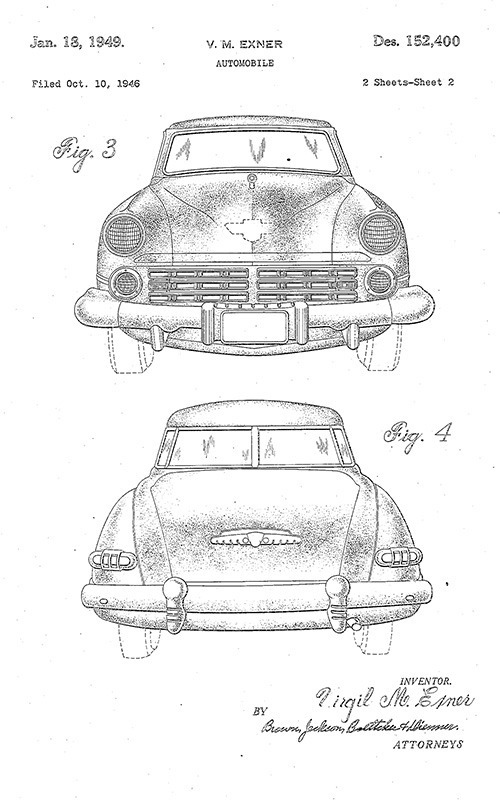

There, Exner was involved in some of their first post-war car designs and was the final designer of the celebrated 1947 Studebaker Champion Starlight coupe. Although Raymond Loewy received the public recognition because his illustrious name had more marketing appeal, Exner is actually listed as the sole inventor on the design patent. Conflict and ill will between the two drove Exner to leave Studebaker. However, Roy Cole introduced Exner to executives at Ford and Chrysler for potential jobs.

U.S Patent USD152400S for Studebaker’s Champion Starlight coupe, Inventor, Virgil M. Exner. Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office.

1947 Studebaker Champion Starlight Coupe. Source: Studebaker National Museum Archives.

In 1949, K. T. Keller, then president of Chrysler Corporation, hired Exner to the post of Chief of the Advanced Styling Studio, a brand new department that would be led by Exner. As noted by Peter Grist, in his book “Virgil Exner: Visioneer,” Chrysler at the time had a reputation for solid and well-engineered cars, but boring styling. The hiring of Exner was an attempt by Keller to combat Chrysler’s dull styling reputation. This was a reputation that Keller was largely to blame for himself, as he excelled at production management, but not styling.

Upon observing the 1948 Cadillac’s fighter jet-inspired tailfins, Exner used fins as a key component in his vehicle designs. Though he liked how they looked on the vehicle. he was also certain of the fins’ aerodynamic advantages. He performed wind tunnel testing at the University of Michigan and, according to his son Virgil Jr. as quoted in Grist’s book “Virgil Exner: Visioneer,” the tailfins “moved the center of air pressure back, a little closer to the center of gravity, providing more inherent directional stability.” Exner gave the automobiles a sleeker, smoother, and more aggressive appearance. By sloping the roof toward the back of the car and leaning the top of the grille forward, he gave the vehicles a sense of being in motion while standing still. In 1955, Chrysler unveiled “The New 100-Million Dollar Look,” a reference to the cost of development and retooling.

By May 1955, all Chrysler cars were using the “Forward Look” logo and slogan. Both may have been dreamed up by a New York advertising agency, but the inspiration was Exner’s designs. The wedge-shaped styling of the Chrysler 300 letter series and updated 1957 models, with their long hoods and short decks, catapulted the business to the forefront of design, with Ford and General Motors scrambling to follow up and mimicking Exner’s designs. The 1957 Imperial was also the first production automobile to employ compound curved glass. In 1957, Exner was elected the first vice president of styling at Chrysler.

1955 Plymouth Belvedere Convertible. Source: Brian (stock.adobe.com)

It wasn’t just American automakers who were attempting to copy Exner’s design style. Carrozzeria Ghia, the Italian automobile design firm, was contracted to create a car for Volkswagen that would ultimately become the Volkswagen Karmann Ghia. Ghia had previously prototyped Exner’s Chrysler D’Elegance and K-310 concepts, and their design for the VW Karmann Ghia had notable stylistic parallels to those concepts. According to Peter Grist, in his book “Virgil Exner: Visioneer,” when Exner saw the Karmann Ghia in 1955, rather than be upset about the plagiarism, “he was pleased with the outcome and glad that one of his designs had made it into large-scale production.”

Unfortunately, after hearing a report that GM was making their vehicles smaller, Lester Lum “Tex” Colbert, Keller’s successor as president of Chrysler, ordered Exner to make the same changes to his 1962 designs. Exner objected to the modification, believing it would make his cars “ugly.” Exner and his colleagues had finished the second full-sized, finless Plymouth since 1955, this one scheduled for 1962 and praised as an incredibly beautiful car. While he was still recuperating from a recent heart attack, Exner’s 1962 models were downsized by associates. The automobiles’ look was significantly altered by this reduction. The cars were less appealing, leading to a significant decrease in sales.

The GM rumor proved to be untrue, and buyers didn’t like the smaller Plymouth and Dodge 1962 models, which had strange style in comparison to more subdued Ford and GM offerings. Chrysler fired Exner because they needed a scapegoat, but they let him stay on as a consultant. Tailfins were soon out of style. Chrysler’s “Forward Look” designs ended with the 1961 models; Exner later dubbed the smaller, finless 1962 Plymouth and Dodge models “plucked chickens.” He thought the management at Chrysler had picked away at the automobiles to reduce their price.

After being fired by Chrysler, Exner decided to pursue his passion for boating by designing boats and cabin cruisers. Eventually he worked with Buehler Turbocraft, designing their 1966 Bolero, 1966 Bar Harbor, and 1967 Express Cruiser. The Bolero was chosen by Popular Science magazine as the “Trend setter for ’66” and the Bar Harbor became one of Buehler’s top sellers. Furthermore, all of these boats are coveted today, showing that Exner’s designs clearly still resonate.

Along with his work on boats, Exner also continued to consult with car companies at this time. Starting in the 1960s, collectors began buying up old Rolls-Royce, Mercedes-Benz, and Bugatti cars. In early 1963, Exner was interviewed by Esquire magazine about this trend and how he thought it affected current and future automotive design. For the piece, Exner designed what he thought some of those older cars would look like with modern styling, which he called “Revival Car” concepts. This led to him being involved in the revival of Stutz in the 1970s as Stutz Motor Car of America, specifically his design for the 1971 Stutz Blackhawk. The Blackhawk was a hit with A-listers, owned by Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, and Dean Martin, and it seemed like everybody who was anybody in 1971 was trying to get one.

1957 Chrysler 300C. Source: Stellantis North America.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.