“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

Car designers have a lot of brain synapses firing. Some designers are driven by the pursuit of beauty, while others are motivated by the pursuit of speed. Giorgetto Giugiaro, Marcello Gandini, and Battista Pininfarina, though responsible for cars that raced, were masters of proportion, flowing curves, sharp angles, and striking aesthetics. Conversely, Adrian Newey, Gordon Murray, and Colin Chapman, though they produced street-legal cars, were schooled in drag coefficients, g-loads, and volumetric efficiency on the track—wrestling over tenths of a second.

Among the race set of designers, Colin Chapman’s approach was unique for his time. Where Formula 1 rival Ferrari employed 12-cylinder engines, Colin Chapman, founder of Lotus Cars, looked beyond the powerplant. His mantra, “Simplify, then add lightness,” didn’t just change the way cars were built. It changed how we think about performance itself.

Chapman was a philosopher of motion. He understood that speed wasn’t just the result of power, but of purpose. Every bolt, beam, and brace in his cars was scrutinized for weight and necessity. If it didn’t serve the driver, it didn’t stay.

— Colin Chapman

Colin Chapman in 1965. Photo: Joost Evers / Anefo;, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Born in 1928 in London, Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman came of age in the mechanical aftermath of World War II. While many car designers of the time cut their teeth in shops or paddocks, Chapman studied structural engineering at University College London, a discipline that shaped his lifelong obsession with efficiency. He applied aviation principles to land-bound machines, treating a car not just as a vehicle, but as a load-bearing structure where every component served a mechanical and aerodynamic purpose.

His first car, the Lotus Mark I, was built in 1948 using an Austin 7 chassis, reportedly in a garage borrowed from his then-girlfriend Hazel Williams’ family—a story confirmed in Karl Ludvigsen’s “Colin Chapman: Inside the Innovator.” This was the beginning of what would become Lotus Engineering. By 1952, Lotus was officially a company. By the end of the decade, Chapman was reshaping motorsport.

Chapman’s philosophical approach was to build cars that punched far above their weights. Where his contemporaries employed V8 or V12 powerplants, Chapman shunned brute strength, focusing more on mechanical efficiency and weight reduction. His Lotus Eleven is a case in point. In competition from 1956 to 1958, the Eleven dominated its class at Le Mans, winning the 1,100cc class in ’56 with Reg Bicknell and Peter Jopp driving. In ’57, with Herbert Mackay-Fraser and Jay Chamberlain behind the wheel, Team Lotus pulled a double, winning the 1,100cc and 750cc classes. Thanks to a slippery aerodynamic body developed in collaboration with aerodynamicist Frank Costin, the Eleven, propelled by its Coventry Climax four-cylinder, routinely beat larger-displacement competitors. The Circuit de la Sarthe was good to the Lotus crew in 1958 as Chapman and company won the 1,500cc class in a Lotus Elite, a fiberglass-bodied grand tourer.

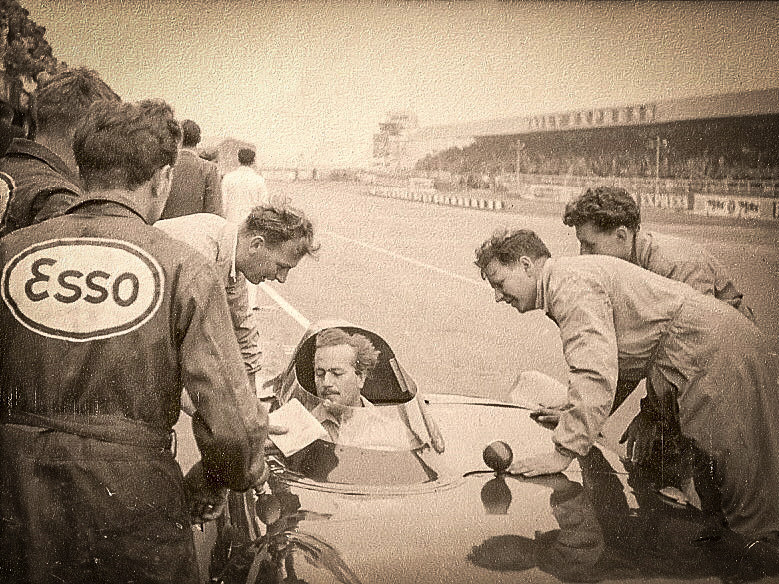

Colin Chapman early in his career. Photo: J Crosthwaite, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Debuting in 1960, the Lotus 18 caried on, giving a young Jim Clark his first taste of Formula 1 success. The Lotus Coventry Climax four-cylinder had grown to include displacements of 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 liters.

But it was the Lotus 25 that turned Chapman into a legend. In 1962, he introduced the first monocoque chassis in Formula 1. A monocoque-type chassis is a tub that replaces the traditional spaceframe with a stressed skin design, making the car’s body and structure a single, integrated shell. As Doug Nye notes in “The Story of Lotus, 1947–1960,” this design increased rigidity while drastically reducing weight, making the car both safer and faster, “Chapman didn’t just redesign a car. He reinvented how cars were made.”

With Jim Clark at the wheel, the Lotus 25 won seven out of 10 races during the 1963 season, securing both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships for Team Lotus. Every F1 car since owes its basic structure to Chapman’s vision.

For some, having such a big moment would be the zenith of their career. For Chapman, the monocoque was the start of the rise, not the apex of the arc.

Lotus Type 25. Photo: Lotus Cars.

Thanks for reading Part 1! Stay tuned next week for Part 2.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.