“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

In Part 1 of this piece, we looked at Colin Chapman’s career up to the mid-60s. In this part, we’ll pick it up in 1965.

In 1965, Chapman and Clark teamed up and made more racing history, this time across the pond at the Brickyard. Their weapon of choice was the Lotus 38, engineered specifically for the Indy 500. The car featured a mid-mounted Ford V8 engine and a lightweight monocoque chassis, a radical departure from the traditional front-engine roadsters that had dominated Indy for decades. Clark demonstrated the car’s superior balance, handling, and speed, leading most of the 500-mile race and winning easily. The Lotus 38 was truly a game-changer, signaling a seismic shift in American open-wheel racing. A front-engine Indy racer never won another 500.

With his innovation still at full throttle, Chapman introduced the Lotus 49 in 1967, and it was one of the Englishman’s most groundbreaking Formula 1 racers. The car’s design incorporated the engine as a fully stressed chassis member. It was not just any engine.

Signaling Lotus’ move to eight-cylinder power, the Lotus 49 debuted the legendary Cosworth DFV, a 3.0-liter naturally aspirated V8. The Cosworth DFV, or Double Four Valve, introduced in 1967, went on to become the most successful engine in Formula 1 history.

Built by Cosworth with Ford’s backing, the DFV didn’t just come out swinging; it landed a knockout blow its first time on the track as the Lotus 49 and Jim Clark won the ’67 Dutch Grand Prix. The Cosworth creation powered cars to 155 Grand Prix victories between 1967 and 1985, dominating the sport and defining a unique era in which privateer teams could be competitive thanks to the DFV’s widespread availability.

The engine’s role as a fully stressed chassis member meant the powerplant was bolted directly to the monocoque while also securing the rear suspension. This concept reduced weight, improved rigidity, and quickly became the standard in Formula 1 engineering.

In 1968, Graham Hill hot-shoed the Lotus 49 to both the Formula 1 Drivers’ Championship and the Constructors’ Championship, in what was the first full season for the Cosworth DFV engine. Although Jim Clark had already secured victories with the 49 in 1967, his untimely death early in 1968 left Hill to lead the campaign.

The hits kept coming as Chapman dropped the Lotus 72 in 1970. It was another radical step forward in Formula 1 design, featuring side-mounted radiators that allowed for a wedge-shaped profile, inboard brakes to reduce unsprung weight, and torsion bar suspension. It was one of the most successful F1 cars ever, staying competitive for six seasons and delivering multiple championships, including Drivers’ titles for Jochen Rindt in 1970 and Emerson Fittipaldi in 1972, as well as three Constructors’ Championships for Lotus.

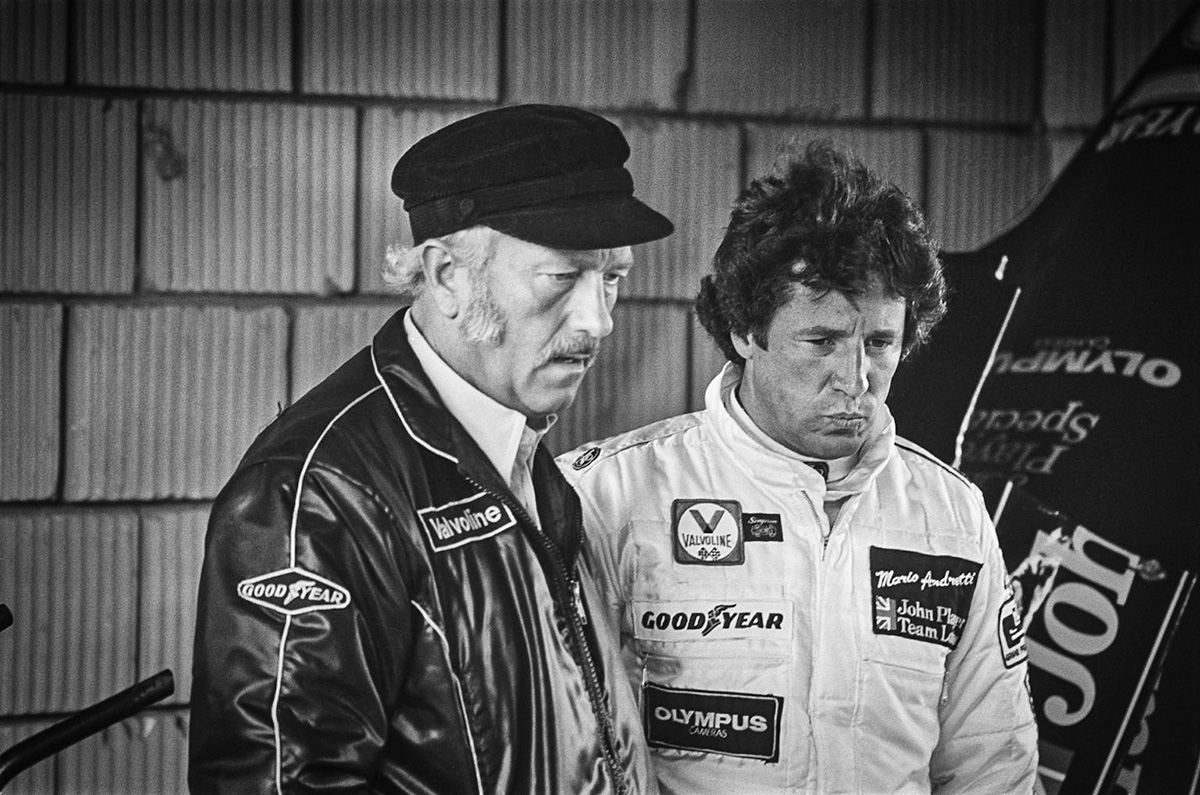

The Lotus 78 and Lotus 79 carried that innovative spirit into the aerodynamic era with the introduction of ground effects. The 78 pioneered the concept in 1977 by using venturi-shaped sidepods and skirts to create downforce without excessive drag, while the 79 perfected the concept with cleaner execution and greater stability, becoming known as the first true “ground effect” car. Mario Andretti drove the 79 to the 1978 Drivers’ Championship, and Lotus claimed the Constructors’ crown. These cars not only dominated their eras but also forced the rest of the grid to adopt ground-effect principles, again reshaping Formula 1 for decades.

Chapman’s innovation wasn’t limited to the racetrack, as Lotus produced street-legal, race-focused cars dating back to the late 1950s.

The Lotus Seven, introduced in 1957, was extremely light, tipping the scales at a scant 1,100 pounds. The car was motivated by a Ford 1.0-liter or 1.2-liter inline-four engine producing roughly 40 to 60 horsepower, depending on the model variant. Thanks to its minimal weight and responsive chassis, the Lotus Seven could deliver performance that belied its modest engine output. It was so pure in purpose that Caterham still builds it today, almost seven decades later. There is an active community of replica Lotus Seven builders, too. These homebuilts are called Locosts.

In the 1960s, Lotus’ road car designs were developed by a dedicated team, though Chapman always retained the final word on major decisions. The design of the original Lotus Elan, introduced in 1962, was led by South African–born John Hickman in collaboration with John Frayling. The Elan featured a steel chassis and fiberglass body, a formula that became a signature of Lotus design. It was motivated by a 1.6-liter twin-cam inline-four engine producing around 105 horsepower, allowing the car to accelerate from 0–60 mph in roughly 8 seconds with a top speed near 125 mph. Its lightweight fiberglass body and nimble suspension gave the Elan exceptional handling, making it one of the most agile and driver-focused sports cars of its era.

1962 Lotus Elan. Photo: Lotus Cars.

In 1966, Lotus unveiled the Europa, a featherweight, mid-engine sports car designed for exceptional handling and aerodynamic efficiency, with a fiberglass body and innovative engineering for its time. John Frayling was the main designer on the project. Powered initially by a 1.5-liter Ford-based engine, the Europa’s mid-engine design was unique, making it a distinctive and driver-focused alternative to more conventional sports cars of the day.

When Lotus introduced the Type 75 Elite in 1974, it marked a daring new chapter for the brand. Styled by Oliver Winterbottom, the sharp wedge design broke from convention, giving the four-seater GT a futuristic presence that stood apart from Lotus’ lightweight two-seaters. Beneath the fiberglass body sat the company’s hallmark steel backbone chassis. Motivation came compliments of the advanced all-aluminum Lotus 907 DOHC inline-four, delivering about 155 horsepower through a five-speed manual or optional automatic transmission. True to Chapman’s vision, the Elite combined balanced handling and precision with everyday usability, offering four-passenger comfort and a more luxurious interior than any Lotus before it. Though its radical styling divided opinions at the time, the Type 75 Elite, which was produced until 1982, has since earned recognition as an ambitious and innovative milestone in the company’s engineering evolution.

The Lotus Esprit (1976) was the most iconic road car produced while Chapman was alive. The Esprit, styled by Giorgetto Giugiaro, is a Hollywood hero—famously transforming into a submarine in the James Bond movie The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). The car initially featured a 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine producing around 160 horsepower, enabling a 0–60 mph time of approximately 7.5 seconds and a top speed near 140 mph. Later turbocharged versions, like the Esprit Turbo and V8 models, boosted output to over 350 horsepower, cutting 0-60 times to under 5 seconds and pushing top speeds beyond 170 mph, all while maintaining the car’s sharp handling and mid-engine balance.

Chapman and Andretti at 1978 Dutch Grand Prix. Photo: Koen Suyk / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Colin Chapman passed away unexpectedly in 1982 at the age of 54, leaving behind a legacy that reshaped both motorsport and road car design. His relentless pursuit of efficiency, innovation, and performance forever changed how engineers think about weight, structure, and aerodynamics, proving that clever engineering often outpaces raw power. From revolutionary Formula 1 cars like the Lotus 25, 49, and 79 to iconic road cars such as the Seven, Elan, and Esprit, Chapman’s vision continues to influence automotive design and racing philosophy today.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.